THE 1960 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN

When LBJ ran against John F. Kennedy for the Democratic nomination in 1960, there was an obvious contrast in age and style. JFK was youth personified—that was his image—and LBJ countered with his seasoned experience. His campaign slogan was “A Leader to Lead the Nation,” and he used that famous profile photo (the correct side) with a little gray in the temples. He worked that to his advantage, insisting that every now and then you needed someone with a touch of gray in their hair, a sign of maturity. His approach was “Kennedy is a young senator, but I’m the Senate majority leader.”

KTBC covered the 1960 primary from the Texas perspective, especially when LBJ was having a function in Austin. There was an aura about The Man. Trailing after him with cameras, we knew we were a part of history being made.

Our station was a very interested observer of the Democratic Convention in Los Angeles, when LBJ was selected as vice president. I wasn’t there; I watched it on television. We knew the players on the Texas side. His trusted aide and the future governor of Texas, John Connally, was a key supporter and a leader in LBJ’s effort for the nomination.

LBJ and JFK hadn’t been enemies, but they were combatable. (Bobby Kennedy despised LBJ until the day Bobby died.) To butcher an Ann Richards analogy, JFK was born on third base, and LBJ was born in the dugout. There was an enormous difference in their personalities, upbringing, culture, and geography. And yet they knew they had to come together to map a strategy for the Democratic campaign against Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge.

After he was selected as the VP running mate at the July convention, LBJ took the Texas Capitol press corps to the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, and I was fortunate to be invited. The White House press corps was also there covering the discussions. The two running mates considered the occasion an opportunity to get to know each other better in a casual setting and in a different light.

When I arrived, the Kennedys were throwing a football on a grassy lawn leading down to the waters of Nantucket Sound. It struck me as a summer home where everybody was on permanent vacation. The presidential candidate and the vice presidential candidate were wandering around the lawn, and the press was observing their every move.

The public scrutiny didn’t seem to bother the Kennedys. They didn’t appear to be posturing; they were being themselves, wearing sneakers, khakis, and open-neck shirts. Their press conferences were informal, un- like those in previous administrations and today, where everything is well scripted. When JFK approached the press corps to make a statement, he didn’t wear a tie or a jacket, per tradition, usually just a golf shirt. He was open and direct about their plans: “Lyndon is going to work the South, and here are a few other things we’ve decided on.”

On one occasion, Jackie Kennedy very graciously came outside to say hello to the press. What a beautiful lady! She was pregnant with John Jr. at the time, and she was positively glowing. Like everyone else in the country, I was impressed with her. She wasn’t trying to make headlines; she was simply an elegant and charming hostess greeting her guests. She understood the importance of good relations with the media.

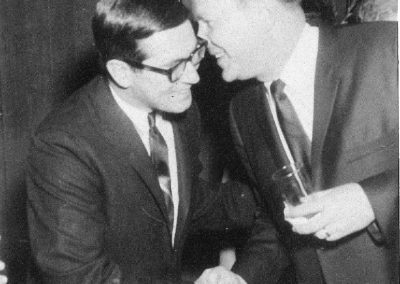

There was a special moment for me when I was standing with both JFK and LBJ on the porch at the compound, and LBJ asked, “Neal, you want to get a picture with us?”

“Well, sure.”

Vern Sanford, who was the Texas Press Association’s executive director, was there with his camera. “Vern, come over here and take a picture,” LBJ said.

Sixty years later, it’s hard to believe, but I actually appeared in a photograph with LBJ and JFK. It’s an absolute treasure—the young Neal Spelce standing between two monumental figures in twentieth-century American history who would eventually serve as presidents of the United States. And there I am, shaking Jack Kennedy’s hand and looking into the eyes of Lyndon Johnson.

Back at KTBC, everyone saw the photo and a joke went around the station: “Neal, you certainly know who your boss is, don’t you?”

LBJ ASCENDING, 1961–1963

Once LBJ became vice president, his Secret Service detail was in and out of the KTBC building in Austin all the time. We had some fun with them. I owned one of those retractable pointers that professors use, and I would get on the elevator with the agent assigned to elevator duty and pull out the retractable pointer like a walkie-talkie and speak into it—“Secret Service on the elevator, stand by”—and collapse the pointer and put it away. Their heads would jerk around. When I went into the lobby: “In lobby now. Secret Service clearly visible.” I would do that every time there was a new agent, and I was lucky they didn’t throw me to the floor.

I had been to the LBJ Ranch for small events before he became vice president, but it was when he served as VP that the ranch became a folksy, comfortable gathering place for world leaders and a familiar geographical reference in the public mind, like Hyannis Port and Warm Springs, Georgia. And of course, when he was president, the ranch became known as the Little White House.

LBJ loved hamburgers made at the Night Hawk, a beloved institution among Austin’s most popular restaurants. The original place was located at the south end of the Congress Avenue Bridge and had been in business since 1932. Harry Akin was the owner and later elected as mayor of Austin, and he was an early supporter of LBJ. Every time the Johnsons hired a new cook, LBJ would phone Harry Akin and tell him, “Harry, I have someone I want to send down there. I want you to teach him how to make those burgers like you make them.”

LBJ’s favorite was the Frisco Burger, with its Thousand Island–like special sauce on a buttered and toasted bun. After the cook was trained, LBJ would sit in his suite above the KTBC studio and eat Frisco Burgers the way they made them at the Night Hawk.

Harry confided to me that LBJ was the one who told him to integrate the Night Hawk. He said, “You’ve got to lead on this, Harry. We’ve got to serve Negroes.”

Harry had already been hiring minorities to work in his kitchen and as wait staff for many years, but serving African American diners was a bolder step during those volatile times. When he decided to integrate his restaurants, there was no muss, no fuss. He just did it. I don’t remember anyone making a peep.

During that same period, in the spring of 1960, African American students from UT and the historically black Huston-Tillotson College had begun to conduct sit-ins at the lunch counters downtown on Congress Avenue at Woolworth’s, the Kress five-and-dime store, and other variety stores and department stores. In Austin, there were demonstrations on both sides of the integration issue, but by May of that year, thirty-two lunch counters and restaurants in Austin had voluntarily desegregated. It was a relatively quick and peaceful transition.

LBJ really did surprise people. As a southerner, he was able to push for social progress and accomplish many things that were not expected of him. Observers assumed that a northeastern liberal like JFK would lead the charge on progressive social issues, but it took a liberal southern Democrat to get things done. He achieved significant success because he’d come up through the Senate and knew how to twist arms. Literally! I’d seen him do it. He would lean over you with that large physical frame and tell you exactly what you needed to do or say.

With Lyndon Johnson serving as vice president and later as president, Austin was becoming more visible in the national consciousness. When- ever world leaders arrived, they’d have to land at Bergstrom Air Force Base (now Austin-Bergstrom International Airport) outside Austin and then be driven or choppered out to the ranch in Stonewall, Texas, which is sixty miles away. The ranch had a small runway that could handle two- engine planes, but not the larger ones. Whenever LBJ or someone else was due to land, the Secret Service would rush out to the landing strip and chase the deer away so there would be no mishap while the plane was touching down.

In time, Austin became an extension of the ranch itself, not only be- cause of the proximity, but also because the White House press corps would stay in Austin when there was a newsworthy event at the ranch. They usually stayed in the Driskill Hotel downtown, and besides their coverage of LBJ, they soon they began writing sidebars about the charming college town.

Previous presidents didn’t have a colorful ranch. LBJ owned cattle and horses and an expanse of land along the Pedernales River. (The proper Texas pronunciation of that river is PURR-de-NAH-liss.) He provided deer hunting and exotic game. By Texas standards it was little more than a gentleman’s ranch, but he had a ranch foreman to make it official—and the barbecue was fantastic.

LBJ had great fun with his visitors. He enjoyed entertaining them. I could see him get a twinkle in his eye whenever he was about to pull a prank on the tinhorns. He loved to drive around his ranch and check on his cattle, and on a few occasions I went along for the ride. He owned a small German-made Amphicar convertible, lagoon blue in color, that could float and maneuver on water. But he didn’t tell his guests it was an amphibious vehicle. They’d get in the car and he’d say, “Let’s go look at the ranch. I’ll show you my cattle. I’ve got this bull out here you gotta see.”

The Pedernales River flows through the ranch property and runs over a little dam, and although passengers can’t see this from a car, the water is streaming over the top of a road. LBJ would drive along, talking about his property and pointing out its woodsy features to the visitors, and then he’d suddenly head straight into the moving water. They didn’t know he was driving on a little strip of road. At other times, he’d shout that the brakes had failed and he’d steer the car splashing into a small lake. While the terrified passengers were catching their breath, he would laugh and guide the amphibious car toward dry land.

BOTH SIDES JOURNALISM

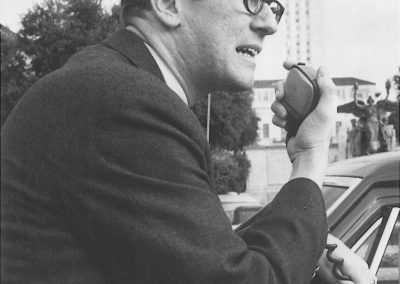

When Barry Goldwater was running against LBJ in 1964, the Republican presidential nominee booked a campaign stop in Austin, in the heart of LBJ country. Goldwater was a pilot, and he flew his own plane, a fairly large DC-3. We reporters headed out to the old Mueller airport in East Austin, and when Goldwater rolled to a stop on the landing strip, we were out there with our cameras. His sup- porters were there, too. He pushed open the pilot window and stuck his head out and waved to the crowd. “I’m glad to be here,” he said. “When I took off from Phoenix, they asked me if I’d ever been to Austin and if I knew where it was. I said, ‘No, I’ve never been to Austin, but I’m gonna fly east and when I get to a fairly good-sized city with only one TV tower, I’m going to land.’”

Folks were amazed that I put that on the air because it was “critical of LBJ’s family ownership of the KTBC-TV station.” But I said, “It was a great quote.”

In all the years I was working at KTBC as a reporter and then as news director—making decisions about what stories to air and what not to air—never once did LBJ or the Johnson family give orders to cover this and not that. There were newsworthy events at the LBJ Ranch, and we’d go out there with reporters from all over the nation to cover a prime minister or some other visiting dignitary. That was news. But we were never told “you must come.”

In one case, Walter Jenkins, one of LBJ’s trusted aides, was arrested for a sexual liaison in a men’s room in Washington, DC, and it was a serious scandal. Mrs. Johnson was very supportive of Jenkins, but in spite of her objection, President Johnson accepted the aide’s resignation.

I ran with the Jenkins story on the air, and the next day I received a call from Time magazine. “Spelce, we’re just checking around the coun- try to find out how this Walter Jenkins story was covered. How did you cover it in Austin?”

“We led with it at ten o’clock last night.” The caller said, “You did?”

“It was the top news story of the day,” I said, “so we led with it.”

They were trying to find out if KTBC had buried the story because it was negative toward LBJ and his family. Our coverage was indicative of how we handled the news at KTBC, even when it wasn’t advantageous to our owner.

That objectivity had been instilled in me by the University of Texas School of Journalism and by Paul Bolton. He was a stickler for getting a story accurate before putting it on the air. Get it first, if at all possible, but get it right, and let people draw their own conclusions based upon what you report. Don’t hide it, don’t dodge it. If it’s out there, it’s out there, and it’s your job as a reporter—as someone who’s conveying important information—to present the facts. The topic doesn’t matter. You want the viewers to say, “Wow, I didn’t know about that.”

Today, there are so many ways for individuals to get news. With the Internet and twenty-four-hour cable news, viewers can go anywhere and find whatever they want to find, with whatever stripe they may want to put on it. But back in the 1950s and 1960s, KTBC was the sole source for television news in Austin and we had a serious obligation to cover it accurately and make sure the facts were correct. I always tell folks, “Don’t rely on a single source. Whenever you’re looking for news, broaden your scope. If you want to watch a left-leaning channel, watch a right-leaning channel as well, so you can balance your judgments and make up your own mind.”

In today’s world, that attitude is considered quaint and out of step with current realities. Sometimes I sound like a Pollyanna, even to myself, but that’s the way I roll.

In my view, polarization is a problem in our society. Most people watch or read to reinforce their own worldviews. And although they’re passionately engaged, they’re missing something if they don’t explore various websites and check other programs and read this blog or that article. I love to go to the online aggregator sites that represent different viewpoints and report on a variety of subjects. I encourage people to get a more complete picture, so whatever their position may be, it’s either reinforced or questioned. It’s important to challenge our assumptions and biases.

Now in my seventh decade as a reporter, I’m often asked, “What do you think about that story that broke today, Neal?” I usually respond, “I was fascinated by it.” Not believing the story, necessarily, but fascinated by the news itself. After so many years in the business, I’ve found a way of standing back and looking at things philosophically.

I’m intrigued by what the left does and what the right does and how everybody reacts to that. I don’t get caught up in “I’m taking his side, and the other side be damned.” I think it goes back to that journalistic train- ing. You’re trained to walk into a situation, whatever it may be—a city council meeting, a public hearing on rising water bills, a school shooting—and analyze what’s going on, what’s newsworthy, what’s most im- portant to your audience. And then you write the story. You don’t get caught up in “Don’t quote this person, but quote this person.” The pursuit of balance and objectivity has carried me forward throughout my long career.

News analysts are everywhere now, but they’re not really that new. I can remember back in the early days when Eric Sevareid would come on CBS as an analyst and commentator. Dan Rather told me one time, “I envision what happens in Eric Sevareid’s life. I can see him waking up, putting on his robe, padding to the front door in his slippers, and picking up several newspapers and reading through them. And then he gets on the phone and says, ‘I think I’ll talk about this today,’ and calls that person and they go have lunch, usually with a martini. And then Eric comes to the office and sits down and writes his piece and records it and goes home. What a life!”

Dan was out there getting punched in the gut, stalked, and shot at, but there’s Sevareid having a martini at lunch.

To be fair to Eric Sevareid, he’d covered the fall of Paris to the Germans in World War II and later parachuted into Burma from a crashing airplane, so he deserved those martinis, because he’d earned his status as a commentator. I watched his analysis over the years, and I’m not sure he ever took a hard right or hard left position. He’d say, “Here is this and here is this, too, and there’s going to be a big battle over this, and we’ll have to watch and wait and see.”

A turning point in polarization may have come with the popular “Point-Counterpoint” segment of 60 Minutes, which aired from 1975 to 1979, a weekly debate between liberal Shana Alexander and conservative James J. Kilpatrick. It was famously satirized on Saturday Night Live, with comedian Dan Aykroyd (Kilpatrick) often replying to Jane Curtin (Alexander), “Jane, you ignorant slut.” I’m not sure if it was the humorous satire or the “Point-Counterpoint” segment itself, but that formula exploded all over country, a harbinger of the future.

Today there are entire teams of folks out there analyzing, pontificating, and arguing “I’m right, you’re wrong.” It’s sometimes entertaining, but usually produces more heat than light.

After I left daily television, I was often brought back to analyze the voter returns during election night coverage. One evening during a state- wide race, I was sitting on the set with the anchor and co-anchor, and I had my yellow pad and pencil in front of me. As election returns came in, it was my job to announce that at 7:00 p.m., this candidate was ahead, and at 8:00 p.m., South Texas had not been counted yet and voting in Houston was heavy. That kind of thing. It’s what computers do now, but all I had was a yellow pad and a number two pencil.

The anchor sitting next to me wasn’t the brightest bulb on the porch, and when I said, “We’d better keep an eye on this. The margin is narrowing, and it looks like the other candidate may win,” he said, “Really, Neal? He’s been behind all night long. How can you say something like that?” And I very calmly and quietly said, “Because of the trendline and votes that are still uncounted. South Texas is normally going to go in this direction, and they’re not in yet—and that could put this candidate over the top.”

That’s the kind of pad-and-pencil analysis I did back in the day, and that’s the way I like to watch election returns now. But the computers are so far ahead of everybody, they calculate results down to the minute and report, “We can now declare a winner in the congressional district northeast of Dallas.” Not to mention, “Hey, California and the West Coast, the election is already over and we’ve declared a winner. Your vote is superfluous.”

The Donald Trump election of 2016 is a great example of how analysis can go awry. All the ratings and data showed that Hillary Clinton was going to win. I’d been watching a lot of television coverage, and I stayed up to speed on what was happening. Two or three days before the election, I made the comment, “Trump can win this.” I mentioned that to a pollster who was polling for Trump and the Republicans, and he said, “There’s just no way.” But I insisted, “I don’t think the polls are right.”

I’m not claiming credit for predicting Trump’s victory, but when I was seeing such large, passionate crowds at his rallies, I tried to figure both sides journalism out, “Who the heck are these folks who are so angry and engaged?” And I realized that those folks were not being polled because they were “anti- media” and “anti-polling”—“I’m not going to talk.” Nobody looked at their numbers. But sitting back in my armchair and watching news coverage week after week, I could see what was taking shape. So when I made that “bold prediction,” I was dismissed, but it came to pass.

It’s the job of the reporter to analyze what’s happening with a cold eye to the truth. Polling has become essential, for better or worse, to that highly competitive media world that has emerged over the past thirty years. Unfortunately, the polls sometimes drive public opinion instead of the other way around. I have examined polls, and even conducted polls when I ran my PR firm, and I know that you can direct the results by how you phrase the questions.

When John Connally was running for governor of Texas for the first time in 1962, he was not well known and he was running against a sit- ting governor, Price Daniel, who was pretty doggone popular. One of Connally’s tactics was to encourage his supporters to vote early. It was a unique idea at that time, and reminiscent of what candidates do today. His campaign would contact the Austin American-Statesman and other newspapers and say, “I understand there are big crowds at the polling places right now, voting early. You ought to send a reporter out there and find out what’s going on.”

Of course, it was a set-up. The reporters would ask the early voters, “Who are you voting for?” and the response was usually, “I’m voting for John Connally.”

Governor Price Daniel’s response was, “My voters can go vote tomorrow.”

But the overall effect was it looked like an enthusiastic groundswell for this unknown candidate named John Connally. The press was being manipulated by his campaign. It wasn’t the first time that a political campaign had outmaneuvered an opponent, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Spelce’s memoir, With The Bark Off, A Journalist’s Memories of LBJ and a Life in the News Media, is published by the University of Texas Briscoe Center for American History. It is available in hardcover, e-book, or audiobook on Amazon.com, or wherever fine books are sold. For more info, or for a personally signed, first edition copy of the hardcover version, visit NealSpelce.com.

The Society Texas conversation continues with Neal Spelce, author of With The Bark Off, in this exclusive interview…

Lance Avery Morgan: Neal, With The Bark Off is the name of your new book. Can you share the background on that title and why you chose it?

Neal Spelce: With The Bark Off is a phrase that I first heard inside the LBJ library, used by Lyndon Johnson. He was talking about what was going to be in his presidential library that was then just getting ready to open. The grand opening had so many important people in attendance, including presidents, in the audience. I thought was such a neat phrase. He was saying that in the library, everything is there. In other words, nothing was hidden…it’s all there. He said that it’s not going to just show the joys and triumphs, but the also the sorrows. So, when I started writing this memoir, it’s straight forward. It’s all true. Everything that I write is true…with the bark off.

The very first time I heard that phrase, LBJ walked up to me just before the ceremony when the library opened. He said, as I followed him to the bathroom, “Neal, I want you to listen to my speech.” I said, ‘All right, sir, be glad to.’ He started reading his speech on three by five cards. What he said about the library was true…it was with the bark off.

LAM: You two never missed a beat with each other, it seems. LBJ is a big part of your book and he was a big part of your life. Tell me about that if you don’t mind, Neal.

NS: We’re kind of re-living it through this memoir, but I first saw LBJ when I was a 12-year-old barefoot kid in Raymondville, Texas in 1948. I heard this helicopter outside and a voice come over a loudspeaker saying, “Come on down to the softball field, we’re gonna have a little rally.” It turns out it was LBJ campaigning in 1948 for the U.S. Senate. My brother and I stood there, fascinated by a helicopter, which we had never seen before.

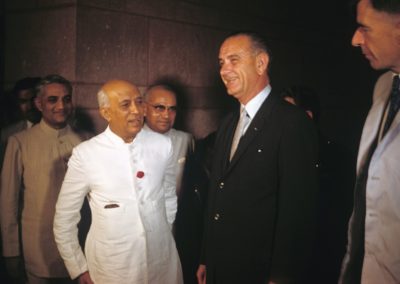

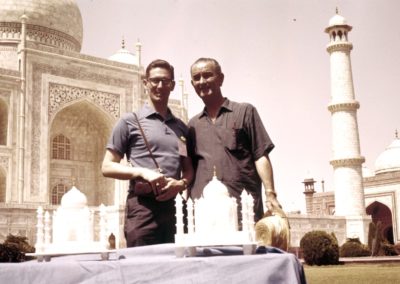

Fast forward to when I got to the University of Texas, I had a fantastic professor named Dewitt Reddick, who knew I was interested in broadcasting, journalism, and television. This was in 1956. He told me that Bill Moyers, working at KTBC TV in Austin, was getting ready to leave. “Do you want me to recommend you?” he asked. I said, “Oh, hell yes.” So, I was hired at KTBC, which was owned by the Lyndon Johnson family. The first time I met LBJ face to face was after I started working there on a part-time basis as a news writer. Paul Bolton, the news director said, “Do you want to meet the Senator?” LBJ was the senate majority leader at the time, and I was in awe. I don’t remember much about the initial meeting, except that he told me, “Neal, I just want you to know that whenever you shoot a picture of me, this is my good side,” as he turned to his left. From then on, I started covering him as a senator, vice president, and president. That included covering (and following him) to Vietnam, India, Pakistan, and events out at the ranch. He was a larger-than-life presence who had a huge impact on me.

LAM: LBJ really made an impact on the world. As I read in your book, he seems to have made significant impact on you and your career.

NS: I think he would have made an impact no matter who he was. Sure, he was impactful by virtue of the offices that he held. But, later, LBJ had an impact on me as a person. I followed him to Hyannis Port, Massachusetts when he was just nominated with John F. Kennedy….I was part of the press corps there. Here I am, with John F. Kennedy and LBJ, and he says, “Neal, come on up here. You want to get your picture made with us?” The same thing happened in India where he met with the Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. He asked me to join him in a photo at the Taj Majal. I never did follow him to the White House. But after he got back to Texas, he hired me to help with the dedication of the LBJ Library. Actually, I was paid by The University of Texas because the school built the LBJ library. They asked me to chair the library opening event, which was a six month job. I worked with him daily, and out at the ranch, in meetings to get the opening going. So, he was quite a presence. At that point, I wasn’t as overwhelmed by him because of the familiarity by being around him so much. No question he had an impact on my life. A bunch.

LAM: You write about LBJ throughout the book, which is especially touching to me, because you two are both larger than life personas that represent Texas. So, it was really terrific to get to know you, and LBJ, more through your writing.

NS: This book is about people and the extraordinary experiences that were opened up to me, particularly by LBJ. I will tell you that the book is not about politics, as you well know. The book is about personalities and politicians, with LBJ being the most dominant because I had the longest and closest association with him, although not on a political level. Instead, it was a personal level and on a reporting level. So, I never got caught up in any of the politics.

LAM: It shows, as I was reading your book, what a small world this is. You had written about when you were at the ranch with the Johnson family, and touring Fredericksburg, when the German chancellors came to visit the U.S. after JFK was assassinated. My family was one of the founding families of Fredericksburg.

NS: Oh, no kidding?

LAM: It’s such a weird, small world story. My great grandmother passed away on Christmas Eve of 1963. You may, or may not remember this, but LBJ and the chancellor attended my great-grandmother’s funeral while they were in Texas during that time.

NS: Oh, wow.

LAM: Because my family had helped the Johnson family so much over the years, LBJ wanted to show the German chancellors, not only small town America in Fredericksburg with its German roots, but also how people would come together in death of someone who was a German American. My older brothers recall that LBJ, the chancellor, and the Secret Service sat in back of the pews behind my family.

NS: Yes, that was when they went to the church. LBJ felt a kinship to the Hill Country, and nearby, simply because they were neighbors. When LBJ was working to get elected to Congress in the early stages, he worked on developing the Highland Lakes under Franklin Roosevelt by bringing electricity and flood control to the area.

LAM: LBJ made a big difference in a lot of lives and it helped spur the growth of this region then.

NS: Oh, it really did. Your family experienced that human side of him that most people don’t witness of world leaders. Speaking of a small world, that brings a quick little story to mind that further demonstrates what you’re taling about. When I was with LBJ on a trip to Pakistan in 1961, he saw this camel beside the road, with its camel driver. At that point, LBJ stopped the motorcade, got out and walked over and said, “I wanna meet him.” He walked over to him just like he might be campaigning in Caldwell County, or something like that.

LAM: Every handshake is a vote.

NS: Right. But he said to the camel driver, just in passing as he was leaving, “You come see me now.” So, the press picked it up saying he invited this camel driver to the United States. Oh my goodness. It turned into a major publicity coup in the sense that he brought the camel driver here to the ranch in the Hill Country. By example, LBJ made a big to-do about electricity, flood control, and getting water and irrigation into this area and helping the farmers. Then, LBJ he called up his friend Henry Ford and said something like, “Henry, this guy’s got a camel and that camel’s gonna die someday. So can you give him a Ford pickup truck?”

LAM: Can you imagine? That’s so great. I mean that attention to the detail of every person like that. That’s the mark of a great politician for sure.

NS: It really is.

LAM: Neal, you’ve known so many fascinating people, especially from your work in public policy. Tell me about why you found it so fascinating and made a career of it.

NS: Well, you know, that’s a good question. I guess I’ve always been very, very curious and that’s a mark of a reporter. You’ve got to have curiosity so that you want to check into things and find out what’s behind what is happening. With Austin as the state capitol, you’re always surrounded by political activities like the state legislature, even on down to the city council. As a reporter, you always covered those things because they were newsworthy. So, I just literally became wrapped up and intrigued by the people who were involved. Plus, you know, and there were some rascals in that group. As well as statesmen. I knew one guy who was getting ready to run for the U.S Senate as a state senator and he says, “A six-year term in the United States Senate? You could almost be a statesman if you didn’t have to run for reelection that often.”

LAM: Right. Being curious is an asset.

NS: When I went to Columbia University on a CBS fellowship in news and public affairs, I went down and got news credentials at the United Nations because I wanted to be a part of it and see what was going on. That was when Nikita Khrushchev was banging on the table with his shoe. And that’s when Fidel Castro came up to New York City and was a part of the UN General Assembly meeting. Of course, the President of the United States and all the world leaders were there. So, I got inoculated with all of this and you know, for some reason it is just became part of my DNA, I guess.

LAM: Thank goodness it has been because the stories that you reported on have made a real big difference to lots of folks. In your book, you recount with such precision, so many events in your life. Can you tell me how events can shape a journalist’s career…like it has yours?

NS: I go back to my journalism training, which frankly is different from today. You’d jump into a story, and you try to find out as much as you possibly can without bias. Then, you report it and let the people who are reading, or seeing, the story make up their own minds. It impacted me in the sense that I was able to see just about every side to a story and that there are often more than two sides to any given story. I always had a fascination to find out those sides. You know, I covered Barry Goldwater when he ran against LBJ. Sure, I was working for the LBJ-owned TV station, but people didn’t think anything about that. I didn’t think anything about that, either. I mean, here’s a guy running for president, so I say, we’ve got to cover him.

LAM: You must be objective no matter what.

NS: Yes, exactly. And that was maintained throughout, even during the time when I was actually on the UT payroll for the library dedication. While I was working directly, and answering directly, to LBJ on the development of his library, there was no politics involved in that. In fact, we had to advise him, and say, “You know, Mr. President, you don’t have an exhibit here on Vietnam. And he said, ‘Oh my goodness’. And Vietnam was such a big part of his presidency. So, they changed the exhibit.

LAM: Vietnam was such a political thorn in his side for so many years.

NS: As he said, with the bark off. I’m sure Vietnam was painful for him. But he didn’t dodge it. He didn’t want the war and never really saw peace from it. It took a toll on him. I wasn’t involved in his politics. I came to be more fascinated by people, like the Bush presidents, as individuals and public servants, more so than their political leanings. Then, many politicians liked each other, or at least respected each other. Like with Texas governors, Ann Richards and John Connally, both opposite sides of the political spectrum people. I remember at John Connally’s funeral, I walked up to Ann Richards and she said to me, “God, I miss John. He helped me so much when I was governor.” There’s a humanness to these people who have these big titles and big responsibilities. They’re public servants and, human beings. That’s what I think kept me more intrigued and interested in them as individuals, rather than them as political idealogues. Hey, when you sit in a bass boat with two former presidents like the Bushes, with just the three of us fishing, you get a feeling for them as individuals. Plus, I wanted to find out about the relationship of father and son who ended up both leading the free world and I got a lot of insight into them as individuals. That was my main interest.

There’re so much that is a part of people that has kept me fascinated by the political aspect of everything. For instance, John McCain. I traveled with him when he was campaigning for president and worked with him on his speeches, not policy. It was just about how to deliver and communicate. We would have drinks and dinner after a long workday, or go to his hideaway in Sedona, Arizona. He would let his hair down and I asked him how in the world someone could endure five and a half years of torture in a prisoner of war setting like he did.

McCain earlier would ask me, “Neal, tell me about LBJ.” And later I said, “Senator, let me ask you about your time in the Hanoi Hilton.” That was a joking reference to the POW concentration camp. It was quid pro quo with the two of us giving and getting information. So, he talked about the torture and about how his fellow prisoners saved his life when he was at rock bottom and couldn’t even feed himself. He told me that because he had been tortured so horribly, he lost his arrogance. He began his military career as a feisty Navy Top Gun pilot but while he was a prisoner of war, he was broken and learned how to rely on his fellow man. His fellow prisoners saved his life. They kept him alive when he was on the verge of death.

LAM: You had mentioned the phrase, and you don’t hear this very often anymore, public servant. It feels like we’re sort of operating on kind of on a different planet with all the changes going on. And certainly, in Texas, and today’s media world. What are your thoughts about that? Have we progressed, for lack of better terminology?

NS: Well, we’ve certainly evolved.

LAM: Evolved. Yes, that’s perfect.

NS: Now when you hear me say this, remember I’m coming from being an observer, rather than someone who’s involved in it. What I’ve observed is that the world has not only changed, but the method of communication has changed so dramatically and drastically with a 48-hour, 24 hour and even immediate news cycles on your computer, TV sets, and phone. People tend to learn more, but I’m not sure they actually are more educated from what they are seeing. They are getting more reinforcement for whatever biases they start out with. So, to be a public servant, and this is me drawing a conclusion here, you don’t have to appeal to everybody that you used to when you ran for the U.S. Senate in Texas, where the entire state had to be your constituency to win.

That’s carried down to a local level, too. Now, everything is compartmentalized. If you’re a Republican, you only have to appeal to only the Republican base these days. Same with the Democrats. LBJ had a phrase for that. He said, “What we’re striving for is the greatest good for the greatest number.” It has a nice ring to it, but it also is so important for politicians to sit there and realize, ‘Hey, I may not represent those views, but those people have concerns. And I’ve got to be sure I take care of those concerns as well.’ I’m not so sure today that drives public service.

LAM: I agree a hundred percent. Information doesn’t necessarily connote knowledge.

Neal, I’m so excited to be thinking about the second installment of your book next year. Before we end, let me ask you about the UT Tower shooting in 1966 that was such a big part of your career. That must have been a life changing day for you.

NS: It was. The Tower shooting was very emotional for a lot of people. For me, it’s history and cannot be ignored, even as horrible as it was, and is, to this day. I don’t mind talking about it. In fact, I, I feel like we need to talk about it so that we can learn from it and understand it today. You know, for instance, if that event had not occurred as it did, we wouldn’t have had EMS develop as it has today. Or, SWAT teams. There was no way that any police force of any kind anywhere could handle that sort of event then. No one was ready for it. So, it has caused a lot of change in the world. That was the first of its kind…for a guy like Charles Whitman to climb up on top of the Tower in 1966 and indiscriminately start shooting people. No one could imagine what was happening, even though they were standing in the midst of it. They would walk out on the Drag and think ‘what’s going on here’ and bang, there’s a shot and maybe they got shot themselves. In fact, when Claire Wilson, the first victim, by the way, was eight months pregnant he shot her directly in the womb. And then he shot her boyfriend who was walking beside her and killed him. She survived. Who knows what was going through Whitman’s mind.

People all over the campus just looked up and stared at the Tower, still not realizing what was happening. They couldn’t comprehend the scope of it. It was a hundred degree day. Sirens were screaming. People were shouting as gunshots were going off, both from the ground and from up above. The sensory aspect of the whole thing is still hard to describe. It was unreal in that sense. I can still hear and see, and almost feel, what was going on long ago. My job reporting on it was to make sense of what was happening. And I, too, didn’t know. Nobody had any perspective. If it happened today, you would have perspective, but at that time, it was just so horrible and out of the ordinary. And I think that’s the reason people today are still so caught up with it. And, remember, that was 1966, more than a half century ago.

Why do people still recall? Well, the UT Tower is still there. It hasn’t changed one bit, except it has some barricades up at the top that you can’t see from the ground very well. The second reason is it occurred out in the open and our television cameras captured all of that on film. That film is still out there today. In fact, I have shared that film with everybody who wanted to use it. With the Abraham Zapruder film of when JFK was shot, he sold that film to Life magazine and others. He made a lot of money. With this event we gave it all away because it was history. I didn’t view it as a way to make money. And, I became the repository for all that film. Over the years of the last half century, I’ve made that film available to any news organization, or to anyone wanting to write a paper about it. By the way, we re-play much of my live on-the-scene broadcast, the sounds, the interviews and all in the audiobook version of With The Bark Off on Audible.com.

LAM: I’m glad you were there to lend your perspective, Neal, and lend your perspective to everything, with this new book, With The Bark Off. We are all so excited for you and are proud to call you a fellow Texan. It was an honor to speak with you.